By tech@thehiveworks.com

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

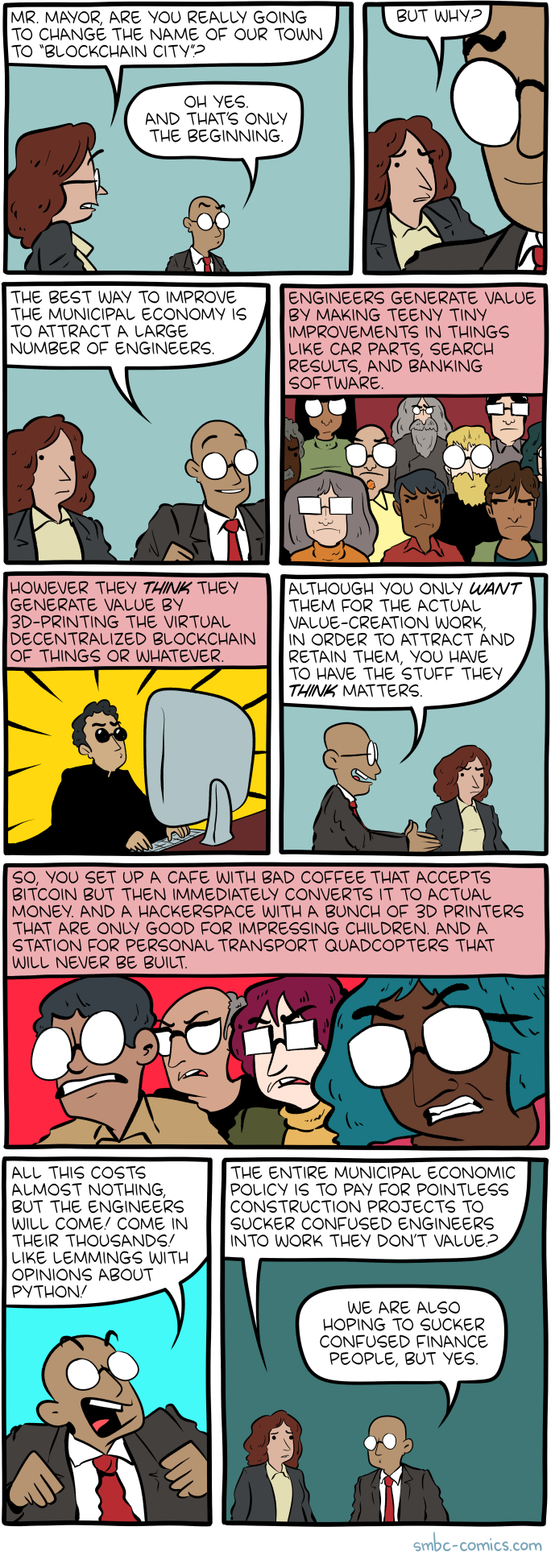

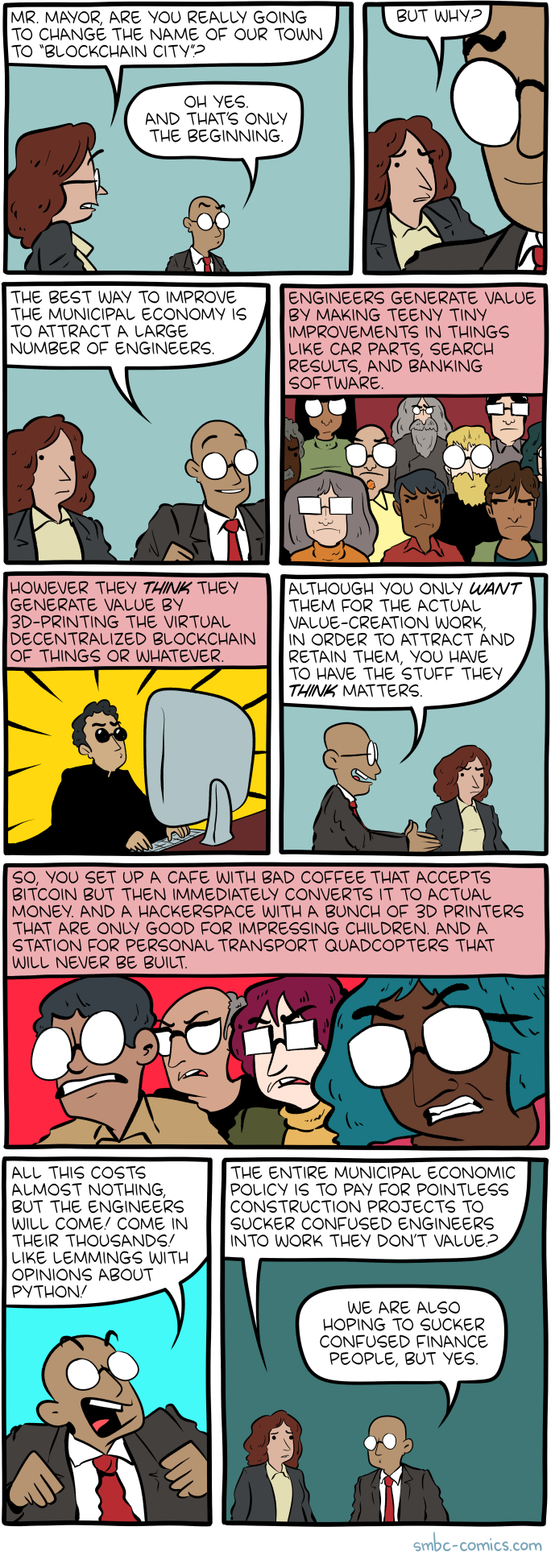

The second step is to get the cartoonists to leave town.

Today's News:

July 25, 2022 at 07:20PM

via Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal https://ift.tt/LwBVzDR

Stay connected with latest and Breaking news.

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Hovertext:

The second step is to get the cartoonists to leave town.

Hovertext:

Be careful not to join the SMBC patreon, because it's got inappropriate-

Men in the US typically do not talk about or worry about birth control that much, to the detriment of the health and safety of women. In the spirit of trying to change that a little, I’m going to talk to you about my experience. About a decade ago, knowing that I did not want to have any more children, I had a vasectomy. And let me tell you, it’s been great. Quickly, here’s what a vasectomy is, via the Mayo Clinic:

Vasectomy is a form of male birth control that cuts the supply of sperm to your semen. It’s done by cutting and sealing the tubes that carry sperm. Vasectomy has a low risk of problems and can usually be performed in an outpatient setting under local anesthesia.

Whether you’re in a committed relationship or a more casual one, knowing that you’re rolling up to sexual encounters with the birth control handled is a really good feeling for everyone concerned.1 Women have typically (and unfairly) had to be the responsible ones about birth control, in large part because it’s ultimately their body, health, and well-being that’s on the line if a sexual act results in pregnancy, but there are benefits of birth control that accrue to both parties (and to society) and taking over that important responsibility from your sexual partner is way more than equitable.

(Here’s the part where I need to come clean: getting a vasectomy was not my idea. I had to be talked into it. It seemed scary and birth control was not something I thought about as much as I should have. I’m ashamed of this; I wish I’d been more proactive and taken more responsibility about it. Guys, we should be talking about and thinking about this shit just as much as women do! I hope you’ve figured this out earlier than I did. Ok, back to the matter at hand.)

Vasectomies are often covered by health insurance and are (somewhat) reversible. These issues can be legitimate dealbreakers for some people. Some folks cannot afford the cost of the procedure or can’t take the necessary time off of work to recover (heavy lifting is verboten for a few days afterwards). And if you get a vasectomy in your 20s for the purpose of 10-15 years of birth control before deciding to start a family, the lack of guarantee around reversal might be unappealing. Talk to your doctor, insurance company, and place of employment about these concerns!

Does the procedure hurt? This is a concern that many men have and the answer is yes: it hurts a little bit during and for a few days afterwards. For most people, you’re in and out in an hour or two, you ice your crotch, pop some Advil, take it easy for a few days, and you’re good to go.1 It’s a small price to pay and honestly if you don’t want to get a vasectomy because you’re worried about your balls aching for 48 hours, I’m going to suggest that you are a whiny little baby — and I’m telling you this as someone who is quite uncomfortable and sometimes faints during even routine medical procedures.

So, if you’re a sperm-producing person who has sex with people who can get pregnant and do not wish for pregnancy to occur, you should consider getting a vasectomy. It’s a minor procedure with few side effects that results in an almost iron-clad guarantee against unwanted pregnancy. At the very least, know that this is an option you have and that you can talk to your partner and doctor about it. Good luck!

Just to be clear, you still have to worry about sexually transmitted infections — a vasectomy obviously does not provide any protection against that.↩

There also is a follow-up about 6-12 weeks later to make sure the procedure worked. You masturbate into a cup and they check to see that there’s no sperm in the sample. Part of this follow-up, if my experience is any guide, includes checking that the doctor’s office bathroom door is locked about 50 times while watching very outdated porn on a small TV mounted up in the corner of the tiny room. It’s fine though! And you have a fun story to tell later.↩

I love this: the local recycling center in the town of Kamikatsu, Japan is itself made of recycled and upcycled materials. Most prominent of those materials are the hundreds of mismatched windows that form the building’s facade:

Brilliant. From Dezeen:

Kamikatsu’s main industry was once forestry, but all that remains of this today are neglected cedar forests. Nakamura’s studio worked with Yamada Noriaki Structural Design Office to design a structure using unprocessed cedar logs that reduce waste associated with squared-off lumber.

The logs are roughly sawn along their length to retain their inherent strength and natural appearance. The two sawn sections are bolted together to form supporting trusses that can be easily disassembled and reused if required.

The building’s facades are made using timber offcuts and approximately 700 windows donated by the community. The fixtures were measured, repaired and assigned a position using computer software, creating a seemingly random yet precise patchwork effect.

Recycled glass and pottery were used to create terrazzo flooring. Materials donated by companies, including bricks, tiles, wooden flooring and fabrics, were all repurposed within the building.

Unwanted objects were also sourced from various local buildings, including deserted houses, a former government building and a junior high school that had closed. Harvest containers from a shiitake mushroom factory are used as bookshelves in front of windows in the office.

The recycling center also includes a “take it or leave it” shop where residents can exchange used goods and a small hotel. (via colossal)

Tags: architecture Japan recycling

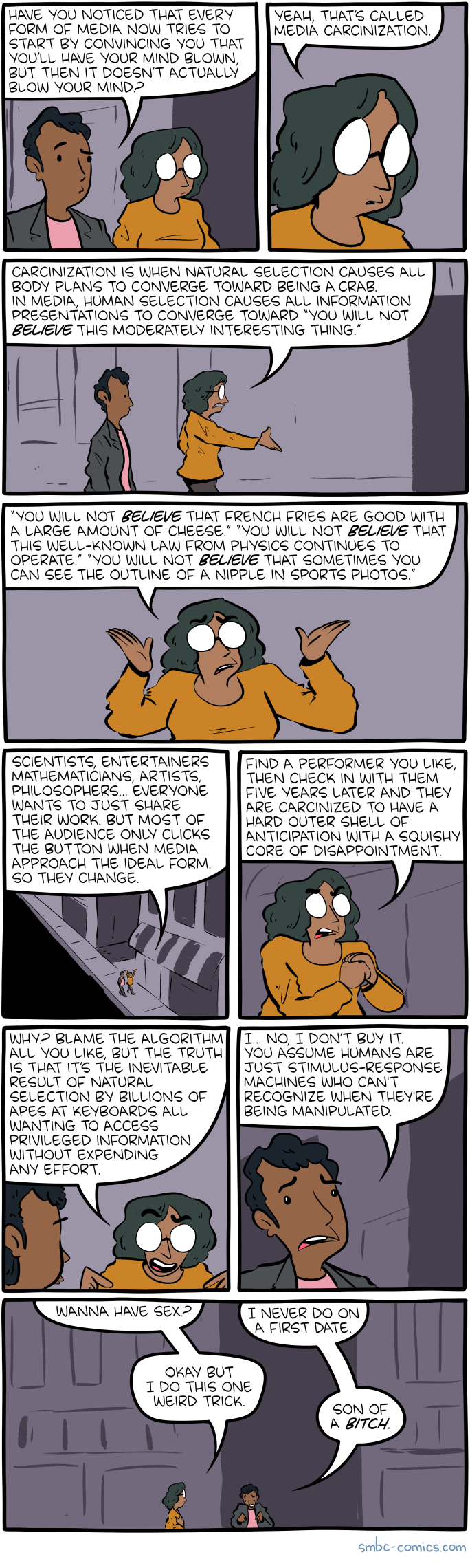

Hovertext:

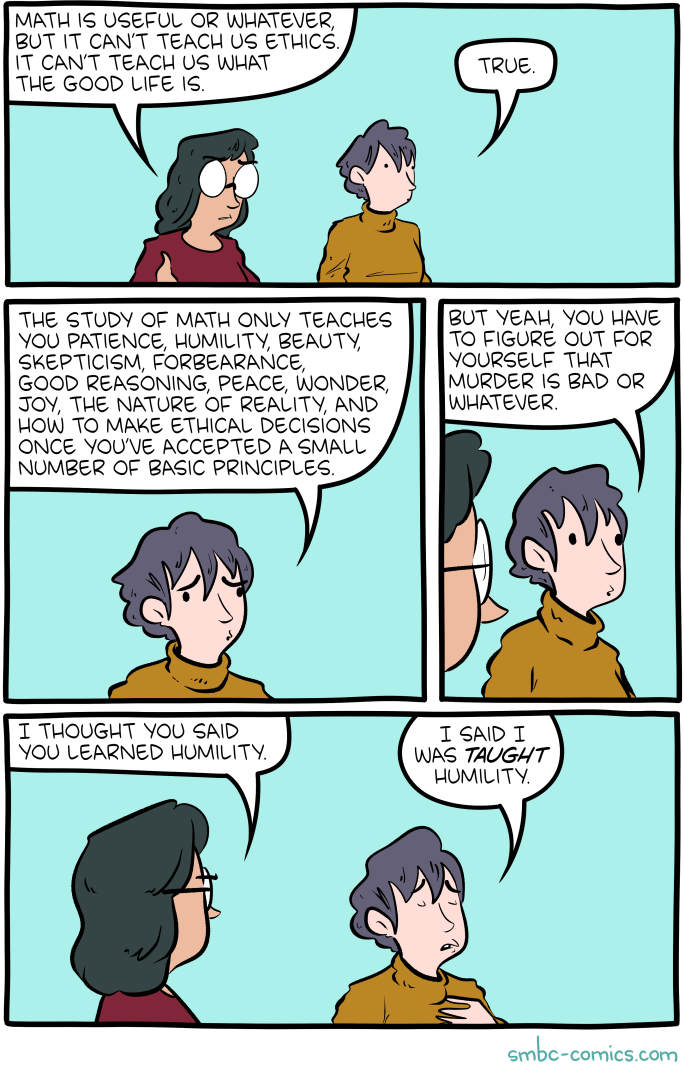

Written after enjoying Francis Su's new book, Mathematics for Human Flourishing, which slightly changed my view about this type of question.

Quick notes before blog:

One: A bunch of you mutants who use RSS noted that it was having weird formatting issues. I've deformatted today's blog before posting. Please let me know how it works.

Two: Thanks for the lovely emails, cucurbit-fanciers. I'm sorry so many of you have had trouble growing them - consider trying gourds or cucumbers or melons, which seem less subject to pests in my experience. One reader recommends looking into tatume squash.

Three: I've gotten some requests to host these posts somewhere so people can cleanly share them. I'm looking into it. My one rule is I don't want it to be the least bit interactive, other than through emails, so a lot of the ready-made blogging sites won't work. More to come.

Theory of the Peak Experience I have a deep bias that VR does not have mass market potential. I think it would’ve been shocking to me circa 1989 that for about the equivalent price of a Nintendo NES you could access a variety of fairly immersive virtual experiences, but it just wouldn’t be that popular. However, I suspect if I’d had the option during Winter 1991 to either play Zelda 3 or a VR immersive version of the same game, I would’ve played a lot more of the regular version. I’d have gone for the VR first, but then would’ve played intermittently afterward. I have a theory about why this is, and I suspect it can be generalized. Note, there are two aspects here: first, the expectation that more high fidelity gaming should be better, and second, the ultimately stronger preference for a more “traditional†video game experience. I think the first part - the expectation part - is easy to explain. Humans, especially nerdy ones, tend to want the world to operate on a High Score basis. Our brain tells us that if you take all the easily quantified parameters and amp them up you should get a better experience. Indeed, there are many venues where this is simply true - a plane that gets to its destination faster and has wider seats and tastier food is a better airplane experience. Other than the seats getting so wide they punch a hole in the plane, you can always drag those stats higher to make the trip better. I think at least some religions and ideologies work on the basis of taking complex things like “what is the good life†or “how do I behave ethically†and converting it to something like a High Score framework, with defined rules and categories of behavior where doing more is always an improvement. How do I live a good life? Good news, there’s scripture and the scripture has a list. The problem lies in assuming just about any experience obeys such a similar framework. And that leads to the second part - why is traditional sit-down gaming actually the more enjoyable option? I think the issue is that while you may have thought sitting on a couch with some snacks and a controller was just a point on the path to a Holodeck level experience, it was actually the peak experience of gameplay. Ideal gameplay does not involve maxing out all parameters. A VR headset is more expensive, more interesting to talk about as a technology, more likely to be featured in a beloved sci fi story, and more futuristic generally, but if the goal is something like pleasure, it is lesser. The ape called Human would generally rather have a comfy chair, a third person view, and only partial immersion, so that they can eat some chips or have a friend drop in. VR maxes out one video game parameter: fidelity. And, for most of us, most of the time, that just isn’t desirable. The reason VR isn’t very popular isn’t a need to improve more - it’s that the actual peak experience came at an unexpected place earlier in the history of game design. I think this also helps explain why so many extremely popular games have purposefully simple/unimpressive graphics - another thing that would’ve shocked early 90s video gamers. The only really strong use case I see for VR is porn, and I think understanding why helps get us deeper into the theory of peak experience. The basic deal, I suspect, is that porn is a subcategory of virtual experience where higher fidelity is genuinely desirable, pretty much always. Compare this to, say, the virtual experience of being a knight. I don’t want the actual experience of a stifling, heavy, multi-layer suit of armor. I don’t want the actual experience of sleeping in the woods unshowered for weeks at a time. I certainly don’t want the actual experience of, say, being stabbed or beheaded. I have not had the privilege, but my suspicion is people who do use VR porn, who I understand are a majority of all VR users period, are there to enjoy a brief high fidelity fantasy. They aren’t looking to be emotionally moved, and to the extent they’re looking for escapism, they don’t want to do it for hours or days at a time. So, porn is like the airplane described above - there are clear parameters and when their scores go higher the experience improves. You know what you want, and when you get more of it that’s better. My guess is that the number of experiences that are porn or airplane-like is fairly narrow. Food is a good example of a clearly non-linear relationship. If you cook a lot, you know that there is always this strong temptation to take an amazing ingredient and max it out. Usually this doesn’t work. Cardamom is delicious, but if you use a ton of it in a pie, it becomes bitter. Olives on pizza are great, but if you overload it you get wet greasy pizza goo. The peak experience doesn’t involve blasting all parameters - it involved getting the right balance. Now, here’s what really interests me. In the case of VR gaming vs. traditional gaming, my suspicion is VR will always be marginal. It’ll be kind of like paintball - there will be ultra-enthusiasts who are super into it, and people who go through phases of doing it a TON, but most of us will see it as a neat experience that we do every once in a while. This is a good thing - humans have recognized what the peak experience was (couch, beer, game) and decided to stick with it. This was not a top-down plan - it’s just that there’s nothing pushing us to switch to a high-tech solution and so we happily have chosen not to. There are cases where this is not true. Or, anyway, not true as far as I can tell. Consider longform letter writing, like people used to do on paper. To be nerdy about it, this form of writing scores high on a lot of parameters I value: writing is very expressive when you use a pen; it’s very intimate; it’s private and you won’t be judged; it’s a long form, so you can be expansive; you have room to qualify your meaning so that you can say things that might be impossible to say in the shy world of face to face contact or the rapid-feedback world of social media. The physical and temporal separation from the receiver gives the thing a savor that even the equivalent sort of email can’t match. The letter goes in the mailbox and you know you won’t hear for a long time. No hovering over the keyboard or looking at a screen. And because you’re not looking someone in the eye or anticipating their instant response, it’s strangely easier to be honest, even sentimental. Plus the fringe benefits: you leave behind correspondence that’s thoughtful and meaningful and made more personal by the use of actual handwriting. Something that maybe descendants of yours will one day read. You also improve as a writer, and as a thinker, because you have to formulate not just short statements, but full cohesive notions. We’ve largely given this up. I have lately started writing long form emails to people, and sometimes even getting replies. With a few people, this has resulted in delightful and ongoing conversations that are unlike anything I could get browsing reddit or twitter or what have you. This was something I had to start doing as a conscious decision and it’s been incredibly rewarding. This leads to an excellent question: what the hell is wrong with me? Why is it that I know what the peak video game experience is, despite not playing many video games, yet I had to get cerebral to identify the peak experience of communication with friends. I think there are three things wrong with me, and likely with you too: first, the speed of email is just pragmatically useful for work. We all appreciate that person who responds to your email in 3 minutes, night and day. Not just because it’s handy - it means projects get done faster, and the world works more efficiently. Conceded - on the parameter of efficiency, email, or email-like messaging systems, win. Second, and related, email and social media offer the chance of instant feedback. Truth be told, most of us would choose rapid reactions positive or negative over the charming experience of just waiting. Note that this sets up email vs. letters as different from couch-sitting vs VR, because videogaming is a pure act of luxury. There’s no reason to ever diverge from the peak experience because efficiency and feedback from friends are not the goal. Third, I’m tied in with you people. If YOU don’t write letters, I have no one to write to, nor to hear back from. I’m in this ecosystem and the habitat is gone. A similar example, I suspect, is singing. People used to sing at home and play instruments for each other. In Darwin’s papers, somewhere he does a cost-benefit analysis of whether to get married, and one of his notes in the plus column is music. To be married was to have music in the mid 19th century. Most exotically to me, men used to gather in pubs to sing together - not as a special thing or a singer’s meetup or an affectation. There were whole books of ballads and such just so you could sing together. There’s an old aviators’ song that goes back to World War I, about a dying pilot, and which would’ve been sung by airmen in bars. I found a version of it online (https://ift.tt/bhq3ajy). Here’s my favorite portion: "Take the magneto out of my stomach, And the butterfly valve off my neck, Extract from my liver the crankshaft, There are lots of good parts in this wreck. "Take the manifold out of my larynx, And the cylinders out of my brain, Take the piston rods out of my kidneys, And assemble the engine again. I love this verse. It’s obscure now, but for me it does everything. It’s a little silly, and you can imagine tipsy pilots singing it in a beer-hall. But it hits two serious notes - one about putting self before others and one about continuing to fight at all costs, both of which I find stirring. Again, this seems to me something like the peak experience of song. No in our imaginary pub sings as well as Celine Dion. You’re lucky if there’s music of any kind, and you can be sure it won’t be hooked to a speaker. But in doing the thing that music does - of unifying the group while moving the individuals - it’s hard to imagine better. Somewhere in his essay collection, Once There Was a War, Steinbeck wrote about how in World War I, the song of the war became the almost-nonsensical Australian ballad Waltzing Matilda, but that World War II hadn’t produced anything like that. When I first read that, I felt foreboding for Steinbeck - from his vantage in the 1940s, he didn’t know he’d already entered the era of mass media dominance. The songs of that war would be from people like George Formby or the Andrews Sisters or Marlene Dietrich. Top down, not bottom up, and I think in a way that was not bad, but which was lesser than the peak experience. Again, it’s clear why you’d move on from the peak experience. Once you can have the Andrews Sisters, how much do you really wanna hear drunk Dave shouting in the pub about crankshafts? Even if you do, it’s so easy to just play a record, rather than having to make your own music. Speaking for myself, as much as I love these old songs, I think it’d feel like it was an affectation. And, again, the habitat for it is gone. With both email and with singing, and I suspect with many things besides, something like perceived quality on one or two parameters moved people from the peak experience to a lesser experience. It’s something that’s been on my mind a lot lately - the other day I enjoyed an essay by Ryan North, where he lamented how in the early Internet you could go whole weeks having only positive experiences on the Internet. Anyone who was around back then likely remembers the feeling. I don’t want to argue that the early 2000s were the peak experience on the Internet - I don’t think they were, mostly because no really knew what they were doing yet. I also worry I’m at the extremely middle-aged risk of imagining my early 20s were the best time on Earth. But, I don’t in fact feel this way - no in my early life wrote letters, and I’ve had to learn it myself. I came around to it due to the discovery that I love epistolary writing collections. TH White and PG Wodehouse are especial favorites, but letter-writing in general was once a great genre of book writing, now mostly gone. I have no nostalgia for it, because I wasn’t around - but I do wish it were still with us. In terms of my own reaction to genuinely sharing Ryan’s feeling that the modern algorithmic and centralized Internet really is worse in many ways than it was in the past, I think it’s more productive to look at individual parts of modern Internet life and see where, in particular, they have fallen short of the peak experience. Those are places where, at least in your own life, you can make repairs. That is in part why I’m doing these blogs. I’ve found that for me, a genuine peak life experience is a good essay by an author I like. Unlike on social media, I find when I read an essayist who’s skilled, I don’t obsess over whether they’re right or wrong. Rather, I enjoy the words and let them shape me. I enjoy inhabiting someone else’s brain for a little while before returning to mine. I don’t suspect I’ve given you a peak experience here, but if you did read this, and it gave you a way of imagining the world that hadn’t occurred to you, or simply had a few clever phrases, you probably had a more genuine, more enjoyable experience than most of the communication you do. If so, consider asking yourself why you don’t do it more often. Zach

Earlier this month, I and others wrote a letter to Congress, basically saying that cryptocurrencies are an complete and total disaster, and urging them to regulate the space. Nothing in that letter is out of the ordinary, and is in line with what I wrote about blockchain in 2019. In response, Matthew Green has written—not really a rebuttal—but a “a general response to some of the more common spurious objections…people make to public blockchain systems.” In it, he makes several broad points:

There’s nothing on that list that I disagree with. (We can argue about whether proof-of-stake is actually an improvement. I am skeptical of systems that enshrine a “they who have the gold make the rules” system of governance. And to the extent any of those scaling solutions work, they undo the decentralization blockchain claims to have.) But I also think that these defenses largely miss the point. To me, the problem isn’t that blockchain systems can be made slightly less awful than they are today. The problem is that they don’t do anything their proponents claim they do. In some very important ways, they’re not secure. They doesn’t replace trust with code; in fact, in many ways they are far less trustworthy than non-blockchain systems. They’re not decentralized, and their inevitable centralization is harmful because it’s largely emergent and ill-defined. They still have trusted intermediaries, often with more power and less oversight than non-blockchain systems. They still require governance. They still require regulation. (These things are what I wrote about here.) The problem with blockchain is that it’s not an improvement to any system—and often makes things worse.

In our letter, we write: “By its very design, blockchain technology is poorly suited for just about every purpose currently touted as a present or potential source of public benefit. From its inception, this technology has been a solution in search of a problem and has now latched onto concepts such as financial inclusion and data transparency to justify its existence, despite far better solutions to these issues already in use. Despite more than thirteen years of development, it has severe limitations and design flaws that preclude almost all applications that deal with public customer data and regulated financial transactions and are not an improvement on existing non-blockchain solutions.”

Green responds: “‘Public blockchain’ technology enables many stupid things: today’s cryptocurrency schemes can be venal, corrupt, overpromised. But the core technology is absolutely not useless. In fact, I think there are some pretty exciting things happening in the field, even if most of them are further away from reality than their boosters would admit.” I have yet to see one. More specifically, I can’t find a blockchain application whose value has anything to do with the blockchain part, that wouldn’t be made safer, more secure, more reliable, and just plain better by removing the blockchain part. I postulate that no one has ever said “Here is a problem that I have. Oh look, blockchain is a good solution.” In every case, the order has been: “I have a blockchain. Oh look, there is a problem I can apply it to.” And in no cases does it actually help.

Someone, please show me an application where blockchain is essential. That is, a problem that could not have been solved without blockchain that can now be solved with it. (And “ransomware couldn’t exist because criminals are blocked from using the conventional financial networks, and cash payments aren’t feasible” does not count.)

For example, Green complains that “credit card merchant fees are similar, or have actually risen in the United States since the 1990s.” This is true, but has little to do with technological inefficiencies or existing trust relationships in the industry. It’s because pretty much everyone who can and is paying attention gets 1% back on their purchases: in cash, frequent flier miles, or other affinity points. Green is right about how unfair this is. It’s a regressive subsidy, “since these fees are baked into the cost of most retail goods and thus fall heavily on the working poor (who pay them even if they use cash).” But that has nothing to do with the lack of blockchain, and solving it isn’t helped by adding a blockchain. It’s a regulatory problem; with a few exceptions, credit card companies have successfully pressured merchants into charging the same prices, whether someone pays in cash or with a credit card. Peer-to-peer payment systems like PayPal, Venmo, MPesa, and AliPay all get around those high transaction fees, and none of them use blockchain.

This is my basic argument: blockchain does nothing to solve any existing problem with financial (or other) systems. Those problems are inherently economic and political, and have nothing to do with technology. And, more importantly, technology can’t solve economic and political problems. Which is good, because adding blockchain causes a whole slew of new problems and makes all of these systems much, much worse.

Green writes: “I have no problem with the idea of legislators (intelligently) passing laws to regulate cryptocurrency. Indeed, given the level of insanity and the number of outright scams that are happening in this area, it’s pretty obvious that our current regulatory framework is not up to the task.” But when you remove the insanity and the scams, what’s left?

EDITED TO ADD: Nicholas Weaver is also adamant about this. David Rosenthal is good, too.

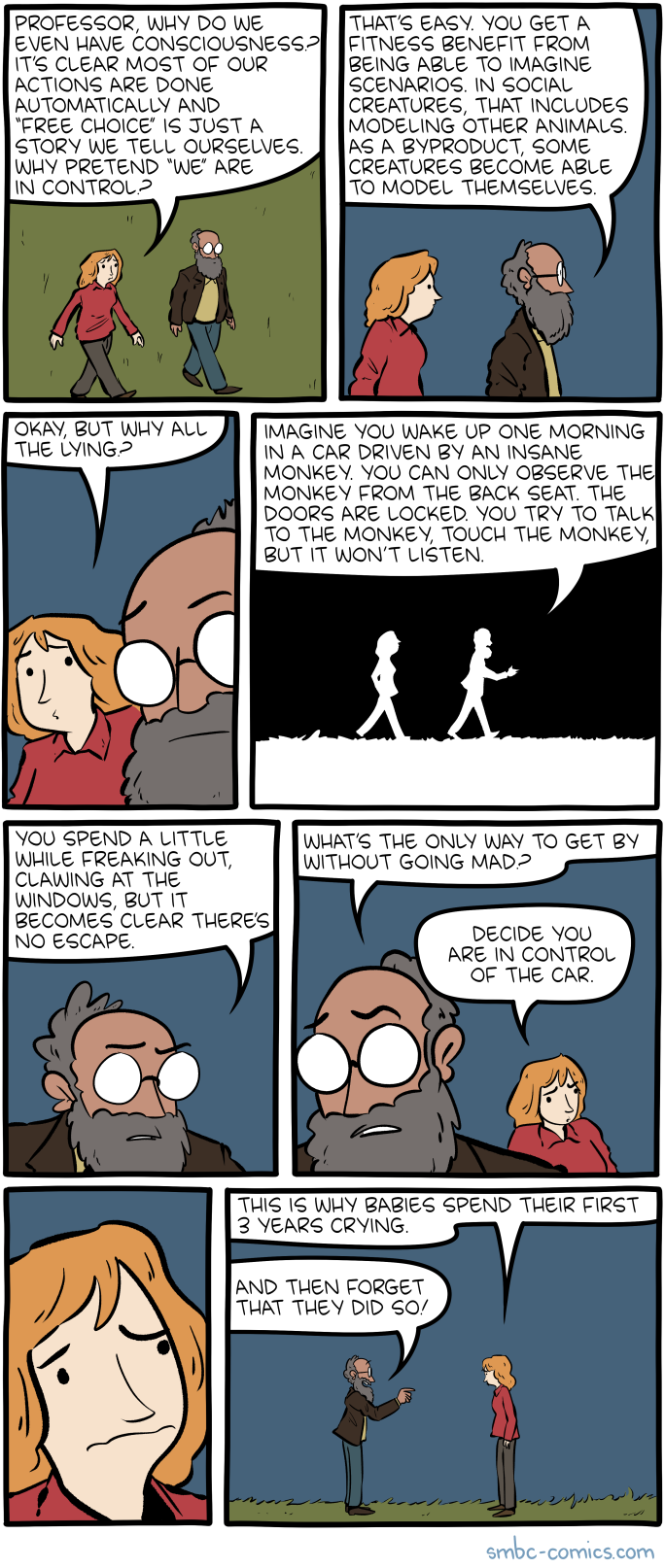

Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal - Consciousness By Zach Weinersmith Click here to go see the bonus panel! Hovertext: Now, realize t...